"Native peoples have found survival strategies during the 500+ years since contact with Europeans. The ledger-art drawings are one example, and this book celebrates the ability of this Northern Cheyenne group to overcome crushing wartime experiences." --- Denise Low

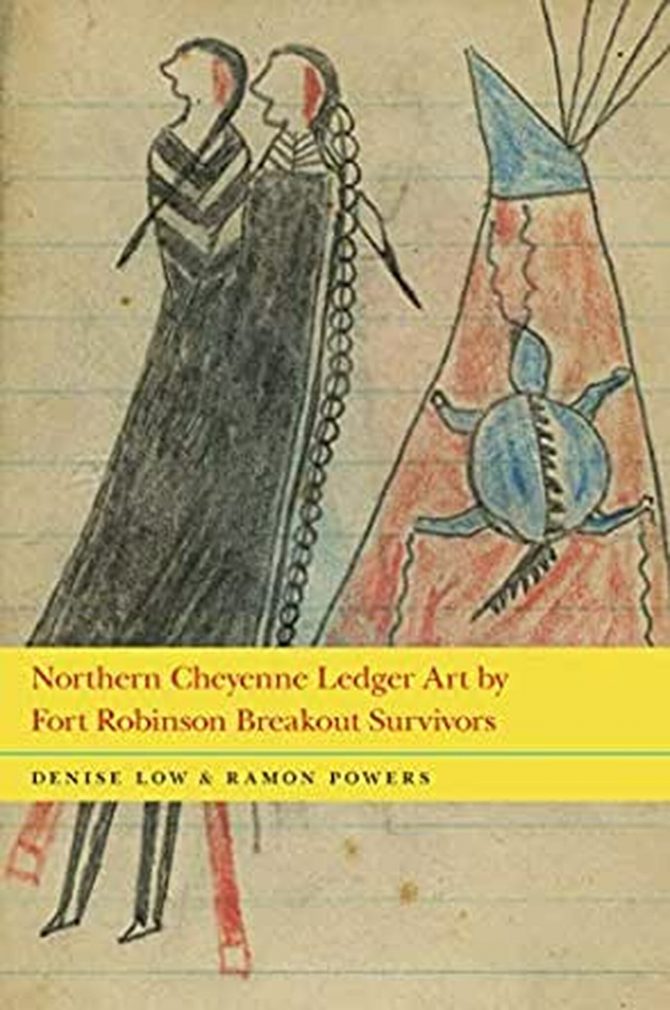

I’m grateful to share a conversation with Denise Low – 2nd Kansas Poet Laureate, professor, publisher and award-winning author. Her new book, co-written with Ramon Powers is Northern Cheyenne Ledger Art by Fort Robinson Breakout Survivors, opens a new window. Ramon Powers is retired Director of Kansas State Historical Society, professor and an award-winning author.

This colorful book honors the powerful resilience and creative resistance of Northern Cheyenne people with cinematic-worthy stories of 19th century history in Kansas, including happenings in Lawrence.

Low highlights the legacy of these Northern Cheyenne ledger artists in a recent blog post about the book. She writes: "Powers and I want our book to celebrate the heroism of these men during the Fort Robinson Breakout, and also afterwards during reservation times, so we provide biographies of them. Some were pivotal in creating the Northern Cheyenne reservation in Montana, in 1884. Porcupine, Strong Left Hand, Old Crow, and Tangle Hair lived into their eighties and were political spokespersons during negotiations with United States agents. Old Crow stayed in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) and fought allotment. One of his descendants’ family stories informs our account."

Denise Low reveals much inspiration in the following conversation. Enjoy!

SB: Would you explain more about ledger art being an expression or form of literacy?

DL: Alphabetic writing is one form of literacy, but not the only one. Who would say that Chinese have a primitive civilization? Yet their written characters are not alphabetic. Mayan glyphs, which I studied briefly, can be written with unique variation according to context. So the number seven, for example, can be slanted or bolded or scaled to create a subtext. The syllable-based glyphs never were written the same. When we speak, especially in the Midwest, we draw out vowels and change pitch to emphasize emotions and meaning. I understand the glyphic systems of the Mayans are a written form of this type of speech. The Plains Indigenous ledger-art drawings likewise modify literal meaning with variations. No exact repetition appears in the Northern Cheyenne ledger-art notebooks, even though some images—female elks with calves, for example—are represented multiple times. Ledger art drawings are highly connotative. They imply narrative and ceremonial traditions that insiders to the culture would understand. They are also like musical scores, in that they guide an oral recitation of the page’s content.

I wrote an article about this, "Composite Indigenous Genre: Cheyenne Ledger Art as Literature", available online, opens a new window. There are also wonderful books that explain this genre in depth, including the works of Joyce Szabo, Temple McLaughlin, Peter Powell, and others.

SB: Were there any surprises discovered during this project?

DL: Many. My co-author Ramon Powers discovered the letter of a doctor who witnessed the creation of a drawing, and the context (ceremonial), and that proved to be very important. This may be the first European-style documentation of how very spiritual Cheyenne ledger art is before reservation times. This is a unique set of texts with repetitions that appear to be more ceremonial than descriptive or narrative. As these aspects of the drawings unfolded, I had greater and greater appreciation for these men and their ability to transform tragedy into new life. The appearance of historic figures like Bat Masterson and Walt Whitman were unexpected, and what fun. I am hoping someone will do the movie.

SB: Are there women ledger artists now or historically?

DL: No. Gender roles for Northern Cheyennes extended to visual genres. Women made geometric patterns, and men made literal representations. This related to their cosmology, where women were Earth-oriented, so the more abstract forms were associated with spirit, the complement. Men were Sky-oriented, so their complement was literal and Earthly. This is a simplification, but it gives the general idea. There were women warriors, and these varied from women who accompanied their husbands to battle as horse handlers and seconds; women who took on warrior roles as women; and women who took on warrior roles identical to men’s. One of these latter was Mochi, who fought dressed like a man, alongside her husband Medicine Water. She was a prisoner of war with the men at Fort Marion in Florida, in the 1870s. Women were respected as givers of life and no matter what role (and that could be fluid), the spiritual identity was primary, as I understand it.

SB: What question do you wish someone would ask you? And would you share your answer?

DL: That question might be, how did I get involved with ledger art. I grew up in the grasslands of the Flint Hills, not far from where Cheyennes raided in Council Grove. Southern Cheyennes hunted and lived throughout western Kansas. So connection to my homeland, and the original inhabitants, is one reason I became interested. Then in the early 1990s, at the Newberry Library in Chicago, I saw the Black Horse ledger, attributed to a great-great-grandfather of Ben Nighthorse Campbell. Sparking - Edward E. Ayer Digital Collection (Newberry Library) - CARLI Digital Collections (illinois.edu), opens a new window. This was a life-changing moment. I became interesting in the narrative point of view of historic events in that ledger compared to what settler historians had written. These ledgers are important sources of Native-centered viewpoints of history and culture.

SB: What are you reading now?

DL: I am reading Beartown, opens a new window by Frederik Backman for my book club. I hope to read the new cookbook Jacques Pépin Quick + Simple, opens a new window. And I have been reading and rereading Carolyn Forché’s new book of poetry, In the Lateness of the World, opens a new window. I have also been rereading Louise Glück’s, opens a new window poems, since she won the Nobel Prize for Literature this year. I have been teaching her for her use of line and for her mythological references.

Cheers to Denise Low, opens a new window for generous insight about your new book! May you enjoy many more inspiring, joyful, and fruitful endeavors!

For further information see Low's blog post, "From the Desk of Denise Low" on the University of Nebraska Press Blog, opens a new window. A related earlier book of note that Ramon Powers co-wrote with James N. Leiker is The Northern Cheyenne Exodus in History and Memory, opens a new window; a Great Plains Distinguished Book Prize winner. And peruse digitized ledger art from The Plains Indian Ledger Art Project, opens a new window of University of California San Diego.

Dear Reader, With this post I divert from my series A Confluence of Writing on Rivers, opens a new window; rest assured I have many more river-connected reads to share around the bend!

Still thinking of rivers, I am inspired to acknowledge traditional Native lands. In our region near the Kansas (Kaw) and Wakarusa Rivers, I want to honor the Dakota, Delaware (Lenape), Kansa (Kaw), Kickapoo, Lakota, Osage, Sac and Fox, Shawnee, and actually hundreds more tribes who find connection here with Haskell Indian Nations University. As Ken Lassman (author of the book Wild Douglas County, opens a new window, and blog Kaw Valley Almanac, opens a new window) noted: “Haskell Indian Nations University is the United Nations of tribes, with members of hundreds of tribes coming here over the lifetime of its existence.”

Acknowledgements

Much appreciation to Denise Low, opens a new window for granting this interview, permission to quote from the blog post, "From the Desk of Denise Low" on the University of Nebraska Press Blog, opens a new window and helping me acknowledge each Native American tribe by their preferred name.

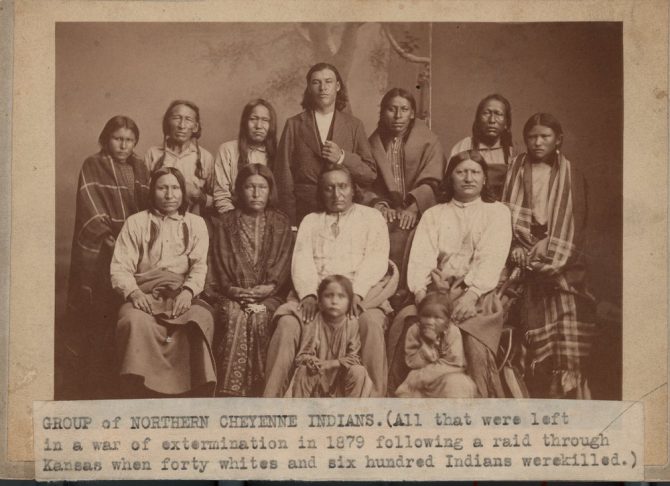

Cover photo of the group of Northern Cheyenne Indians photographed in Lawrence, Kansas in October 1879. Credit KansasMemory.org, opens a new window, Kansas Historical Society, Copy and Reuse Restrictions Apply.

- Shirley Braunlich is a Readers' Services Assistant at Lawrence Public Library.

Northern Cheyenne Ledger Art by Fort Robinson Breakout Survivors

Add a comment to: Indigenous Art As Powerful Resilience and Resistance: Insight from Denise Low