Flying to Florida, looking out from a cramped window seat as we descended over the Gulf of Mexico, I did a double-take. Were it not for my seat belt I would have jumped up and down, for I clearly saw a sperm whale at the surface. I've wondered if my eyes were playing tricks ever since, but recently I found this: "Sperm whales are the only endangered whale to regularly be seen in the Gulf of Mexico, according to NOAA. Fun fact: they are often seen resting log-like at the surface."

I've mentioned before how James Nestor's freediving book, Deep, really got my attention when it described freediving with whales. After his experiences, including being "scanned" by an approaching sperm whale, Nestor was moved to help set up a high-tech effort to understand their language(s), called CETI - the Cetacean Echolocation Initiative.

From the start, A.I. played a central role. Said Nestor, "It’s machine learning, especially, and some A.I. technologies that are currently being used to translate and crack into mouse and bat language. That’s already happening, so the algorithms are all written, and researchers are discovering incredible things. Just to interact with (whales) on a minimal level, I think, would really get people to realize that there’s more happening on this planet than iPhones. There’s something bigger going on here."

That was six or seven years ago. Now, it turns out, there are a lot of people trying to figure out that "something bigger," and some cool books about their efforts are surfacing.

On a Maria Popova "Marginalian" suggestion I read George Dyson's Analogia, ostensibly about evolving technology but presenting much more, and found intriguing discussions of whale talk.

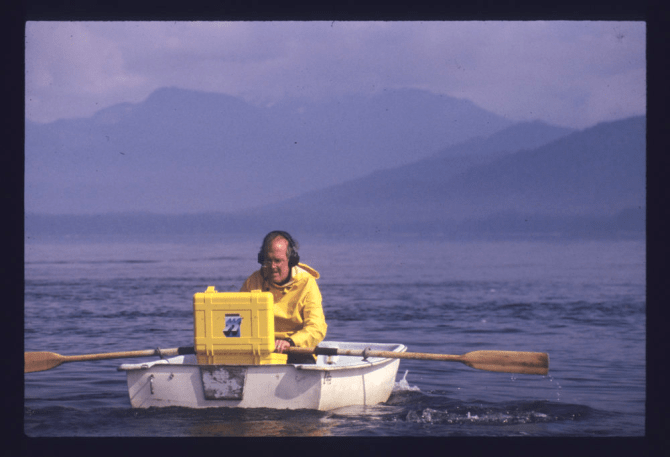

Then, a couple months ago, musician Paul Winter offered a different take, playing his soprano sax to whale song in the middle of Kansas. Not often has such music rolled over the sea of grass, and it took me back many years to repeated listenings of Roger Payne's humpback whale recordings. (BTW, you can now download a humpback whale ringtone.)

Recently I heard sperm whales’ rapid-fire clicking. Imagined it, really, as I read a great new book called How to Speak Whale, by Tom Mustill. This is the guy who went viral some years back when a thirty-ton humpback breached onto his kayak while he was in it. His "voyage to the future of animal communication" grabbed me because it seemed like a perfect sequel to the whalespeak sections of both Deep and Analogia.

Mustill too was inspired by Roger Payne's recordings. He wished he could ask the whale why it did what it did -- intentional? accidental? And why do whales breach in the first place? -- and decided to explore “Whalish,” as another author terms it. Not too surprisingly, CETI figures into his fascinating tale.

There are more books, one so hot off the press that I haven’t seen it yet, and others from earlier in the year: Karen Bakker’s The Sounds of Life, David George Haskell’s Sounds Wild and Broken, and Ed Yong’s An Immense World. There’s also a new and intriguing science fiction title called The Mountain in the Sea. Because octopuses, of course.

These high-tech interspecies communication surveys remind me a bit of Ted Chiang's "Story of Your Life," the alien communication tale on which the movie Arrival is based. Although "Story of Your Life" is more text oriented compared to the auditory explorations mentioned above, they are all undeniably wondrous, and not a little humbling.

Whales or otherwise, I find the burgeoning biology-tech interface fascinating, but at the same time I’m a little apprehensive. Most anything that serves as a gateway for people to better appreciate the non-human world is okay by me, but as a long-time birder still learning to "bird by ear" I wonder if Merlin, the extremely popular app that identifies birds through their songs, will soon have us "talking" to the birds.

I’m not convinced that would be a good thing.

-Jake Vail is an Information Services Assistant at Lawrence Public Library.

Add a comment to: Deep Listening