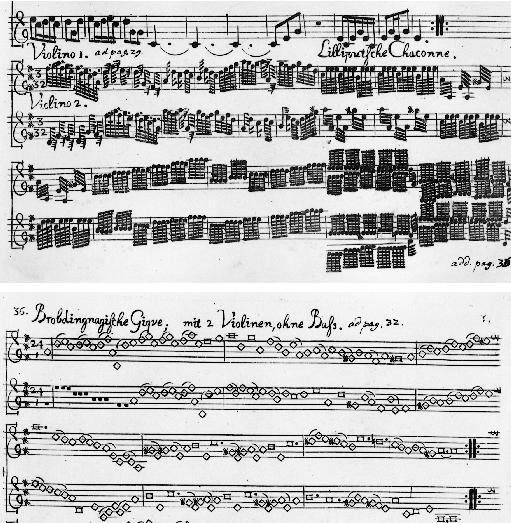

Many of us think of music as notes on a staff - a stark, rigid representation of tones created on an instrument in a universal format of five lines, four spaces, and their octaves above and below.

Through time, this traditional notation has been challenged, modified, and played with. In the Renaissance era, a concept known as “eye music” caught on. Eye music created curious shapes using the staff and its notes, though these modifications were purely aesthetic and often had little effect on the sound of the piece as it was performed.

But in some instances, the piece was considered a type of puzzle to be presented to the performer, and some classifications emerged that were dependent on the design and whether or not the notation was deliberately, unnecessarily difficult to decipher by the performer. Some even included puns of common instructions in the notation in order to create an inside joke between the composer and the performer, completely unknown to the audience (cheeky!).

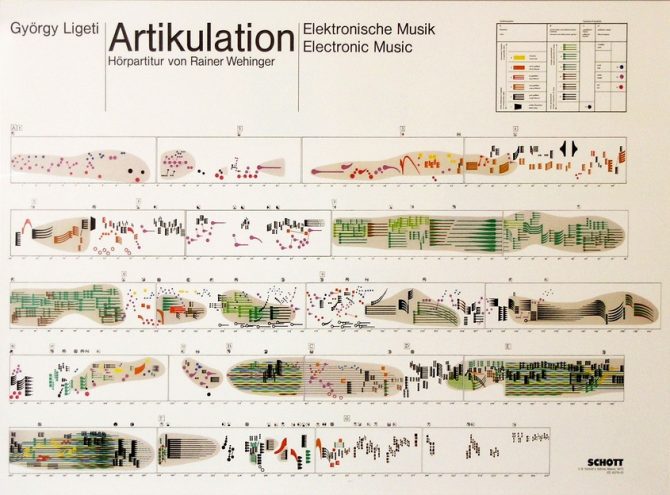

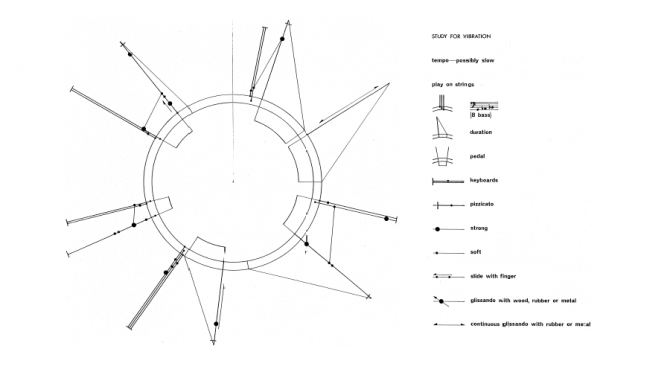

Fast forward a few centuries to the 1950s. Experimental music is beginning to flourish alongside many unconventional approaches to art, and graphic notation starts taking on a new life. In this era, we begin to see musical notation defy all traditional concepts. It is no longer based on the staff with defined notes. It is no longer just black ink on white paper. Notation embraces a total defiance of tradition and enters the abstract.

These emerging ideas of graphic notation start to incorporate beautiful aspects of abstract art and graphic design (with some characteristics resembling Piet Mondrian works and other De Stijl styles from the early 20th century). Gorgeous spires of straight lines intersected with nebulous shapes of solid color, some machine precise in their execution, and some entirely hand drawn with single, spontaneous strokes.

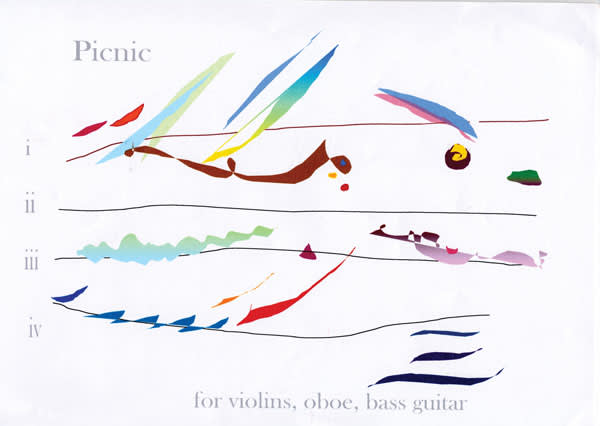

This intersection of visual art and music posited new interpretations of a score. Performers were no longer constrained to defined concepts for performing a piece of music. It was entirely down to their own interpretation. Some graphic scores came with instructions, but many were entirely bereft and encouraged the performer to feel their way through the piece. This leads to entirely unique performances every time - a concept known as "indeterminate music", pioneered by revered experimental composer John Cage. Indeterminate music specifically relies on elements of chance and interpretation to create wholly unique performances. Indeterminacy allows a piece of music to not be a single idea or interpretation, but theoretically infinite. Visually, the pieces live in a singular form, but aurally they exist in profoundly unique interpretations.

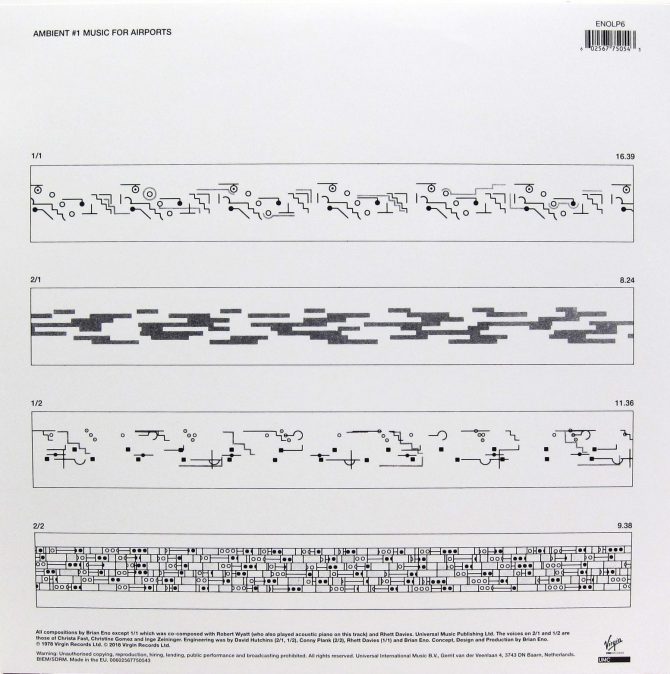

Graphic notation also sometimes holds hands with ambient music. Rather than including a track list on the back of his 1978 album Ambient 1: Music For Airports, Brian Eno (one of the most important names in ambient music and other conceptual arts) chose to make four graphical scores.

Many of these pieces rival the intrigue and quality of any painting or mixed media piece hanging in an art gallery. They simply are gorgeous to look at, and they inspire contemplation of how one can approach music and sound. Of course, this entire approach to music sometimes runs the risk of being a bit too conceptual, perhaps even ridiculous. But so does just about anything if you think about it too hard.

John Cage - I Have Nothing to Say And I Am Saying It

-Joel Bonner is a Technology Services Assistant at Lawrence Public Library.

Add a comment to: Graphic Notation – An Indeterminate Approach to Music