Another scorching summer afternoon and a library patron walks up to the desk: "I remember when we didn't have air conditioning. These are the good old days."

The past, they say, is a foreign country. They do things differently there. Now that our climate catastrophe is changing the world, the present and future are foreign countries as well. Thriving in the future suggests we do things differently there, perhaps by learning from who and what was here before.

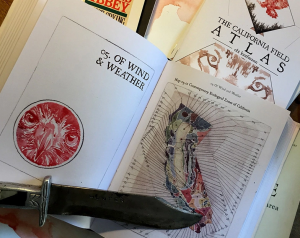

Along those lines, two very different books have grabbed me recently, one about living without technology (!), the other about exploring the place where you live, and artfully describing it. Both by authors doing things differently. Even if that doesn't float your boat, I urge you to read them for brain-jiggling inspiration. They are The Way Home, by Mark Boyle, and A California Field Atlas, by Obi Kaufmann (you'll have to get the latter through Interlibrary Loan).

Boyle, author of The Moneyless Manifesto, has moved from living without money to living without technology. Both sound preposterous, but he manages to find 'the way home,' in Ireland, with aplomb. He also writes well about his journey (using a pencil and paper) without being all preachy. Being a 21st-century developed-world citizen, it should come as no surprise that I found myself surrounded by monetary and technological challenges as I read The Way Home, but rather than making it hard to relate to, such circumstances made the book that much more intriguing. After all, Boyle too is a 21st-century developed-world citizen.

Imagine: no car, no phone, no fridge, no espresso machines. No tunes but the ones you and your friends make. No quick trips to the store -- or anywhere else beyond your neighbor's place. No lights. No Netflix. No air conditioning.

But there are books.

Boyle reads widely, often by candlelight, and so as we meet his neighbors we meet more familiar friends as well: Henry Thoreau, Wendell Berry, Aldo Leopold -- and several we on this side of the pond should become more familiar with: Paul Kingsnorth, Robert Macfarlane, Jay Griffiths, and George Monbiot, to name a few. Boyle, though, doesn't merely name-drop; these luminaries are sprinkled lightly throughout the book and fit in nicely amidst Boyle's tech-less ruminations.

Part of what I find appealing about Boyle's writing is how, despite living a life most of us can't relate to, he frequently and easily makes vital connections, whether cultural, natural, or economic. Perhaps one must, or perhaps it's easier, when making a living free of tech. While repairing his bicycle he muses, "When a man pulls on his brakes in Ireland, whole tracts of ocean and soil are laid to waste in places Western consumers have never even heard of."

"The situation, as always, is complicated," he admits, pointing out that his bike ultimately is dependent on the same flawed global ideology as the car he once owned. So he walks, thinking and observing. This sentence jumped out at me, simply because I don't think anyone else has ever written it, which is a shame:

"I'm meandering through a mosaic of stone-walled fields, trying - failing - to find a pool where two rivers converge..."

And that serves as a perfect segue to Obi Kaufmann's California Field Atlas. Obi, certainly a modern-day Jedi of some sort, is an artist and poet and wanderer of California who I think would feel completely comfortable meandering about looking for a pool where two rivers converge. He's probably done it. And he probably sat down with his kit and painted the scene.

If Mark Boyle is taking us forward by looking back to our agrarian roots, Obi Kaufmann is moving forward by looking even further back -- to dwelling within a wild landscape. Which exists, and will continue to exist, and thus (one suspects he would insist), we should respectfully deal with it. He's here to help us find it, and inspire us to help more of it live.

Kaufmann has therefore devised an ingenious new genre, the field atlas. Not a field guide, though it's full of beautiful watercolors of critters and plants, and not the sort of atlas you'd want if you were driving, for there are no roads. Instead, trails and mountains and rivers and parks and more are mapped (watercolors, not computer-assisted designs) and annotated, with a decided tilt toward the wild.

I can't recommend it highly enough.

-Jake Vail is an Information Services Assistant at Lawrence Public Library.

Add a comment to: The Way Home