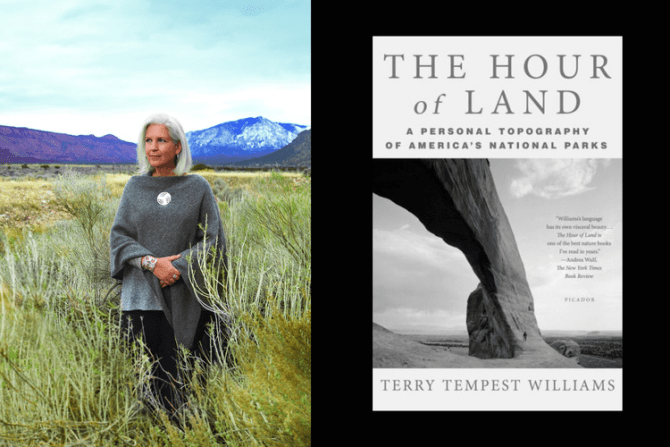

In his last essay, writer Barry Lopez asked, “How can we embrace fearlessly the burning world?” If anyone knows, it may well be Terry Tempest Williams. Terry will be in Lawrence on Wednesday, April 13, though virtually via the Hall Center for Humanities, and again on the 14th for virtual coffee. She'll be talking about one of my favorite books, The Hour of Land. I reviewed it here in 2016, and what follows is an edited mash-up of previous reviews of that book and her latest, Erosion.

How did I not know about the parade of earthen bears marching down the banks of the Mississippi River? The centuries-old earthworks can be found at Effigy Mounds National Monument in Iowa, one of the 423 units of the U.S. National Park Service, and I have writer Terry Tempest Williams and her book The Hour of Land to thank for introducing me to them.

The book takes us on a tour of twelve pieces of the National Park System, from the Gates of the Arctic to the Gulf of Mexico, from Acadia to Alcatraz. It isn’t what I expected – but I shouldn't be surprised. Look at the subtitles of some of her works: An Unnatural History of Family and Place. Passion and Patience in the Desert. Fifty-Four Variations on Voice. Essays of Undoing.

The subtitle of This Hour of Land is “A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks.” The parks, monuments, and recreation areas she visits are not so much described as used as campfires around which we sit while Williams tells their stories. This is where she does her best storytelling, getting personal while at the same time discussing often-hidden histories. Some parks exist because their original inhabitants were removed, she reminds us, as at Yosemite. Deep pockets with agendas have funded parkland acquisition, as at Grand Teton and Acadia. Park stories have changed for the better, too, as at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, originally Custer Battlefield National Monument.

I particularly enjoyed Williams’ visit to Alcatraz National Recreation Area, where she and activist Tim DeChristopher viewed dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s installation, and her descriptions of wildfires in Glacier National Park that trapped her family even while the glaciers receded. To further inspire the reader, The Hour of Land is literally bookended by photos – Carleton Watkins’ 1870s image of El Capitan in Yosemite, and Ansley West Rivers’ 2011 “Lunar Trace” from the Grand Canyon – and each chapter is accompanied by a gorgeous black and white image by a different photographer.

Williams traversed many miles in the course of this book, revealing the sheer diversity and beauty of our parks, and of her writing. Along the way she tips her hat to friends and influences, many of whom will be familiar to readers. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Wallace Stegner was one, who said:

“If we preserved as parks only those places that have no economic possibilities, we would have no parks. And in the decades to come, it will be not only the buffalo and the trumpeter swan who need sanctuaries. Our own species is going to need them too. It needs them now.”

Since finishing THOL, Terry published a great book of essays called Erosion. Despite the title, it's not a gloomy collection -- the opposites of erosion run throughout, sometimes subtly, building hope, empathy, and new perspectives as surely as erosion builds new landscapes. Birds migrate through as well, as is often the case in her writings, and pronghorn and tortoises and prairie dogs.

Though powerfully grounded in her home state of Utah, she continues to get around. She visits Nebraska's Platte River to experience the sandhill crane migration, as everyone must. She frolics with sea lions in the waters of the Galapagos, and watches polar bears in Alaska.

As I finished nearly every essay, I thought "That is such a great essay," and then the next one surpassed it. A couple, though, really stood out: her interview with Tim DeChristopher, and one called "My Beautiful Undoing: Erosion of Self," which kinda erodes your ability to breathe. I liked the surprise ending of "The Council of Pronghorn," too.

Riffing on Darwin while in the Galapagos, she asks, “What if the survival of the fittest is the survival of compassion?” That question is being sorely tested in this age of climate crisis, as she makes clear. In the latter parts of the book, in rather personal explorations of the erosion of fear and the erosion of belief, Terry Tempest Williams’ compassion again comes to the fore.

We who consider ourselves environmentalists too often get lost in hand-wringing and abstract thinking, and forget about simple compassion. Terry Tempest Williams remembers. She knows the joy of life and the pain of death. She also knows of the joy of death and the pain of life, and writes about each with love and amazing grace.

-Jake Vail is an Information Services Assistant at Lawrence Public Library.

Add a comment to: The Hour of Land is Now