Once upon a time, a couple of my friends followed some hawks all the way to Argentina, just to figure out what they do during our winter. Back then, no one even knew where migratory Swainson's hawks went(!). But a Forest Service guy named Brian had wrangled some first-generation transmitters that beamed location information -- once a week -- to NOAA satellites, which he could then access on a big clunky computer.

Brian strapped the transmitters on a couple hawks, promptly lost one en route, but managed to figure out the other's destination. A month later he and my friends followed it (and hundreds of others) south to las pampas. You can read all about it in Scott Weidensaul's 1999 book, Living on the Wind. Then you can get an update on the story of the hawks, on tracking technology, and on many other stories of avian journeys in his 2021 book, A World on the Wing -- my Book of the Year last year. It's been on my mind a lot during the hours I've spent walking and birding during the pandemic, recalling more than once Emily Dickinson's oft-quoted declaration that "hope is the thing with feathers."

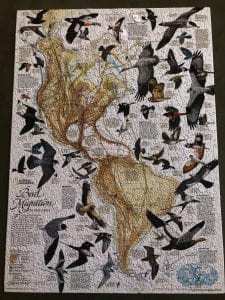

So it was quite a surprise when Mr. Claus migrated down from the North Pole with a National Geographic jigsaw puzzle depicting avian migration of the Americas. In addition to taking me back to my younger days when I had this map on my wall, it reminded me of a great book called Where the Animals Go, by James Cheshire, a collection of 50 fascinating maps that really take advantage of our clever tracking tech.

The Nat Geo puzzle also reminded me that maps are snapshots (perhaps the wrong term for things that have been drawn or constructed for most of the time they’ve existed), and what they depict is subject to change. For example, the Swainson's hawk migration -- new line(s) on the map. Another example: a wondrous essay called "Wildness on a Whim" was recently published by LPL friend J. Drew Lanham, describing the discovery of another piece of the changing migratory bird puzzle, whimbrels gathering just off the coast of South Carolina. Another line on the map, or, as Drew describes it, more stitching on the quilt.

The Nat Geo puzzle also reminded me that maps are snapshots (perhaps the wrong term for things that have been drawn or constructed for most of the time they’ve existed), and what they depict is subject to change. For example, the Swainson's hawk migration -- new line(s) on the map. Another example: a wondrous essay called "Wildness on a Whim" was recently published by LPL friend J. Drew Lanham, describing the discovery of another piece of the changing migratory bird puzzle, whimbrels gathering just off the coast of South Carolina. Another line on the map, or, as Drew describes it, more stitching on the quilt.

Along these lines, there are several new atlases and other mappish books worth exploring. (Atlas, as you surely know, was the Greek god who held the earth on his shoulders. Wrong. Atlas was a Titan who took part in a war against Zeus, for which he was condemned to hold the heavens aloft. Which to me means an atlas should be a collection of astronomical guides. Just the opinion of a mere mortal.)

The Atlas of A Changing Climate, by Brian Buma. Nice images and information.

The Atlas of Disappearing Places, by Christina Conklin. Good idea; poorly executed maps.

Atlas of the Invisible, by James Cheshire et al., the same team that brought you Where the Animals Go.

North American Maps for Curious Minds, by Matthew Bucklan. Geo-Infotainment.

Speaking of curious minds, in Barry Lopez’s short story, The Mappist, a geographer who has finally tracked down a mysterious cartographer says, overwhelmed by his maps, “These maps reveal the foundations beneath the ephemera… there’s so much more.”

“That’s the idea,” replies the mappist.

So much more, and often unexpected: in addition to hawks and whimbrels there are other creatures on the move, but without wings or even legs. I've not seen it yet, but in his new book, THE TREELINE: THE LAST FOREST AND THE FUTURE OF LIFE ON EARTH, author Ben Rawlence describes the changing map of the arboreal north. He's being compared to Lopez -- high praise indeed -- and summaries of "the last forest" also bring to mind Tolkien's legenday Ents on the march:

"We Ents do not like being roused; and we never are roused unless it is clear to us that our trees and our lives are in great danger…"

-Jake Vail is an Information Services Assistant at Lawrence Public Library.

Add a comment to: Maps and Legends