Being nearby to see a bird in flight can be a transcendent experience. The sensation of watching a bird flying overhead has inspired me to simulate my own flight, standing with my arms raised high. And this seems most powerful in a wide-open natural area like the Haskell-Baker Wetlands—in the presence of many red-winged blackbirds.

Being nearby to see a bird in flight can be a transcendent experience. The sensation of watching a bird flying overhead has inspired me to simulate my own flight, standing with my arms raised high. And this seems most powerful in a wide-open natural area like the Haskell-Baker Wetlands—in the presence of many red-winged blackbirds.

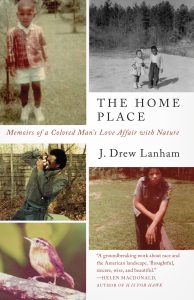

I’ve become more aware recently that most other people out on the nature trails have white skin like me. Author J. Drew Lanham poetically describes the phenomenon of uncommon black or brown companion birders.

His recent book, The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair With Nature, opens a new window, shares lyrically-written storytelling of deep connections to family, his strong sense of place, a passion for nature, optimism and wit along with the frustration of being the singular African American ornithologist in a predominantly white field. Lanham is an Alumni Distinguished Professor of Wildlife Ecology and Master Teacher at Clemson University in South Carolina; he’s also a poet, naturalist, hunter, and birder.

“Birding While Black” is a poignant chapter in Lanham’s book reflecting fears similar to the negative experiences expressed by the phrase “driving while black”. A black man risks being accused of suspicious activity simply for being out in a remote environment.

Lanham writes:

In remote places fear has always accompanied binoculars, scopes, and field guides as baggage. …a white supremacist group [was] “organized” in the mountains of western North Carolina, near the places I was supposed to do a research project. They’d made the national news in stories that showed them worshiping Hitler and shooting at targets that looked like Martin Luther King Jr. Someone at the university joked about my degree being awarded posthumously. So though the proposal had been written and the project was well on its way to being funded—and as potentially groundbreaking the research on rose-breasted grosbeaks, golden-winged warblers, and forest management in the Southern Appalachians might be—I had to abandon the whole thing.

He continues:

I look at maps through this lens—at the places where tolerance seems to thrive, and where hate and racism seem to fester—and think about where I want to be. Mostly those places jibe with my desires to be in the wild but sometimes they don’t.

The wild things and places belong to all of us. So while I can’t fix the bigger problems of race in the United States—can’t suggest a means by which I, and others like me, will always feel safe—I can prescribe a solution in my own small corner. Get more people of color “out there.” Turn oddities into commonplace. The presence of more black birders, wildlife biologists, hunters, hikers, and fisher-folk will say to others that we, too appreciate the warble of a summer tanager, the incredible instincts of a whitetale buck, and the sound of wind in the tall pines. Our responsibility is to pass something on to those coming after. As young people of color reconnect with what so many of their ancestors knew—that our connections to the land run deep, like the taproots of mighty oaks, that the land renews and sustains us—maybe things will begin to change.

I’m hoping that soon a black birder won’t be a rare sighting. I’m hoping that at some point I’ll see color sprinkled throughout a birding-festival crowd. I’m hoping for the day when young hotshot birders just happen to be black like me. These hopes brighten the darkness of past experiences.

Lanham is a terrific ambassador to inspire more people to enjoy the natural world, yet he also recognizes the empowerment shared by people with similar cultural experiences.

Lanham has created several entertaining short videos to advocate his mission of diversifying the community of naturalists; one of my favorites is witty-satire “Bird-Watching While Black: A Wildlife Ecologist Shares His Tips.” Use this link to watch the 2-minute video online, opens a new window, produced by BirdNote and featured in National Geographic Society’s Short Film Showcase.

This is a rallying cry to help more people connect to the outdoors, and I am inspired by Lanham’s message. I will be reaching out to be more inclusive in planning future nature-related events. As a Board Member and volunteer with Kansas Native Plant Society, I have organized and attended many outings over the last 17 years; almost all the folks who have joined me have been white.

We need to be ambassadors to bring more kids and adults together from diverse communities to explore and connect with natural places—to imagine flight and experience transcendence with the birds.

I crave being outside in nature, but I was well into my 30s before I first enjoyed a wild environment. I wish someone had taken me under their wing to share wild places when I was a kid. I’ll be following J. Drew Lanham’s lead; when I visit a natural area I’ll respectfully invite new & old friends of different ages, varied hues and diverse origins to join me. I hope you’ll join me and we’ll exponentially increase the advocates for the natural world!

-Shirley Braunlich is a Readers’ Services Assistant at Lawrence Public Library.

Add a comment to: Birding While Black: Author is Lyrically Rooted In Place With Diversity In Mind