That got your attention, didn't it?

It crawled out of a new book that's so great it derailed my previous plan, which was to review some books about plants and fungi. Maybe next time.

Like you, fellow average human, I'm visually oriented, despite being nearsighted for most of my life. I am slowly getting better at "birding by ear," identifying feathered fauna by listening rather than by their field marks, and occasionally I will try to confirm a plant's identity by its texture or taste (warning: not always a good idea). I admit this because I am humbled, as you will be when you come to your senses and read Ed Yong's new book An Immense World. It's astounding. You, with your hand lenses and high-powered binoculars and hearing aids and birdsong apps (and, ahem, bifocals), you think you have it covered. You have no idea of the unexpected ecologies you're missing out on.

The "immense world" concept is something I was aiming for when drafting the abandoned plants-and-fungi post. There's so much fascinating activity going on around us, we'd all walk around slack-jawed if we could witness it. Hear it. Sense it at all. We might even care a bit more about little things like biodiversity and extinction. Lucky for us, there are smart voices to direct our attention and help translate.

Ed Yong, more writer than biologist, hooked me when he described in the introduction to An Immense World how treehopper vibrations sound like cows mooing. (I can't believe he missed it, but Wikipedia tells me that some treehoppers, bugs that look like thorns, even communicate with geckos this way.)

There's lots of this sort of quirky information out there. If you're a birder, you may have heard that kestrels can see the urine trails of the voles they prey on using ultraviolet-light vision. If you've read James Nestor's book Deep, you know about the sperm whale clicks that travel thousands of miles. If you've read A Kansas Bestiary, you know that boreal chorus frogs hear through their front legs and regal fritillary butterflies smell with their feet. You've no doubt seen articles on how the noises of city life are making birds sing louder, or how artificial lighting adversely affects their migration.

Ed Yong is somehow able to make a big, cohesive, scientifically detailed, and enthralling book that includes all this sort of stuff, complete with extensive footnotes (don't skip over the footnotes), a notes and bibliography section that's a book in itself, and cool photo illustrations.

Before An Immense World, Yong and his many microbes wrote the engaging I Contain Multitudes, and more recently he penned an extensive and Pulitzer Prize-winning series of articles on COVID. Not too many science writers deliver interesting and enjoyable books (early David Quammen and Merlin Sheldrake come to mind), but Ed Yong is now two for two. I think it's because of his approach: while, or maybe because of, digging way down into obscure or just-discovered nuggets, he's aware that nature is "kind of goofy at times but also deeply wondrous," as he said in an interview.

His subtitle, "How animal senses reveal the hidden realms around us," only hints at the scope of the book. Unlike a few other sciencey titles I've browsed, this is no mere compendium of lists. Yong excels in placing things in contexts that readers can appreciate, and despite the challenges of describing all sorts of animal activities and anatomical parts that are beyond our ken, he's great at elucidating the unfamiliar. For example:

"To get an idea of the shape of [the pit viper's infrared-sensitive pits], imagine placing a miniature trampoline on the bottom of a goldfish bowl and turning the whole thing on its side." Pretty clear, right? (Now imagine a couple of those just behind your nostrils.) He then tells us how the arrangement works.

If you were to write such a book, which of the senses would you lead off with? (n.b.: there are way more than five.) Despite our strong visual bias, and because we are but "leaking sacks of chemicals" and he is mostly discussing animals, Yong starts with smell and taste. Besides, sight is really complicated, in more ways than you know, so it gets a couple chapters to itself. Same with touch and sound. While they are all mind-blowing, I feel (heh) the four "touch" chapters, which include pain, heat, contact and flow, and surface vibrations, are the most intriguing.

Keep in mind that the critters discussed live not only on the planet's surface amongst us puny humans, but also underground, underwater, and in the air. They range from microscopic to cetacean. They are unspeakably exotic and rather commonplace. And they definitely have appendages and receptors we don't.

I can't do it justice, so I'm going to wrap up by sharing a few things I gleaned. Make of them what you will, then read An Immense World.

Hugh manatee has a short attention span.

The ocean has a secret topography of scents.

A snake's tongue motion creates two donut-shaped rings of air, sucking in odors from either side.

We see by smelling light.

Male mice make a pheromone called darcin, after Pride and Prejudice's male hero.

The stinger of a parasitic wasp is like a Swiss army knife. It's a drill, a nose, a tongue, and a hand.

Swordfish heat their eyes to speed up their vision.

Catfish are swimming tongues.

One more:

Save the quiet, preserve the dark.

-Jake Vail is an Information Services Assistant at Lawrence Public Library.

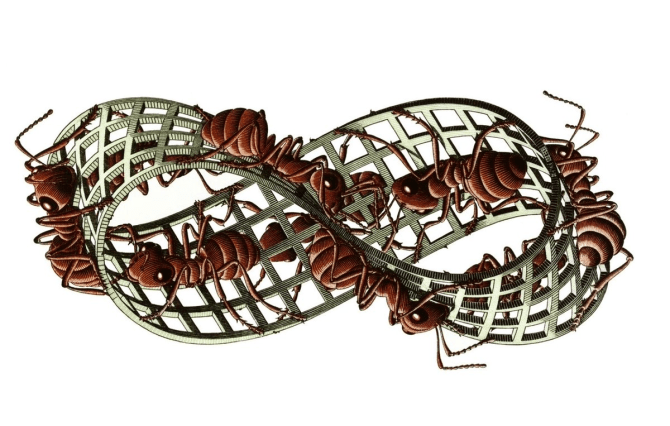

Add a comment to: Ant Pheromone Death Spiral