One of the perks of working at the Ask Desk is how over time one gets to know a good chunk of Lawrence's library-going population. From artists and mechanics, to struggling folks proud to tell you about their new job, to kids and retirees new to town, it's a living version of the Pictures at an Exhibition promenade. But without Baba Yaga's hut.

Recently, an Ask Desk conversation with a KU biologist friend shifted from our usual chat about critters to, believe it or not, books. It turns out that we both often look for books outside of our areas of expertise, and he was looking for a new history book - which we found. My fallback from the usual fare is also history, and failing that, something art related. Or, truth be told, a good spy/detective thriller, a preference he also shares.

Along those lines, in addition to art surveys and art essays and artist biographies, I find books on art thefts and forgeries oddly appealing. It's not so surprising, then, that a new book by a guard at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art caught my eye.

But art theft gets only a quick few pages in All the Beauty in the World, a slow-paced and wonderfully engaging memoir of sorts by Patrick Bringley. Imagine leaving a job at The New Yorker to spend a decade standing quietly amidst great works from around the world, watching tides of tourists and school kids and an occasional artist or scholar file past, and making sure they all behave. I wasn't sure what to expect, but Bringley's writing won me over and I "read" the Met far faster than I would walk through it. Especially if it was a busy day: as Bringley explains, the Met "welcomes almost seven million visitors a year. That's a greater attendance than the Yankees, Mets, Giants, Jets, Knicks, and Nets combined." This sentence alone made me happy, but the whole thing is enjoyable.

Not too many pages in, I realized that part of the reason for my enjoyment, indeed, the feeling of camaraderie with the author, was the fact that I too spend hours on my feet, answering questions, giving directions, and sometimes offering a little history or a recommendation. Another important similarity: you, readers, are patrons, not customers. Though at the library we encourage you to take pieces of the collection home for a while.

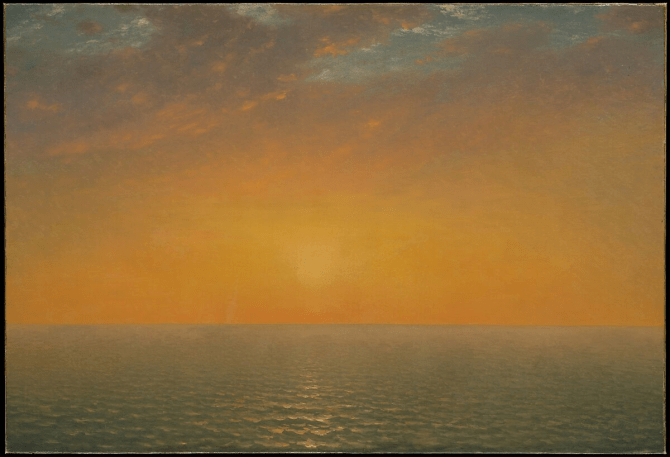

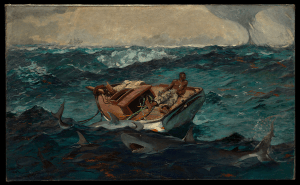

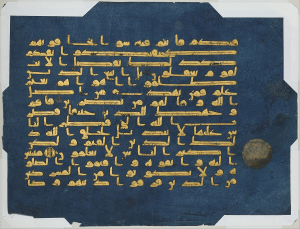

Not your typical "art book," we’re nonetheless are offered good-sized servings of Bringley's perceptive and learned commentary on the art he watches over. Throughout his tale, he often frames his lessons within affable encounters with patrons of all ages and abilities, or sometimes a discussion with a co-worker. His matter-of-fact stories often include snippets of poetry and literature (well, he did work at the New Yorker), but without pretension, as he strives to help us and his patrons learn, as he says, from art, not merely about it.

There are no colorful reproductions in All the Beauty in the World, but in the back there's a list of featured artworks with high-res links to the Met's website - easy to use and certainly worth checking out - plus a helpful bibliography. We are also the beneficiaries of Maya McMahon's sketches throughout, useful as teaching aids and reminders.

Somewhat surprisingly, there are few arguments over artists and quality, or trivial concerns like what kinds of shoes one should wear when standing all day - though we do discover clip-on ties are preferred to the more complicated old-school type, and employees get a hose allowance for new socks. I also expected discussions of provenance and repatriation, but didn't find too much. And that's fine in a book like this.

In closing, and at the end of his tenure as a Metropolitan Museum of Art guard, Bringley offers a few thoughts on art and suggestions to the reader/museum goer. But rather than spoilers, I’ll end with an observation made by one of his coworkers upon his own retirement:

"It really isn't a bad job. Your feet hurt, but nothing else does."

[Note: Images, works mentioned in the book, are from the Met's website]

-Jake Vail is an Information Services Assistant at Lawrence Public Library.

Add a comment to: All the Beauty