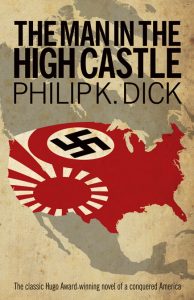

Amazon released an original series adaptation of The Man in the High Castle, Philip K. Dick’s classic depiction of a postwar world ruled by the Nazis and Japanese. Hearing this, I headed for the basement to track down my old copy, a paperback on the inside cover of which I had scrawled my name and “1995,” the year I read it.

No wonder all I could remember was how much I loved it. Twenty years on I’ve finished it again, just as the calendar marks passage of another anniversary: the 70th since the end of World War II.

Set in the San Francisco of a 1962 that never occurred, The Man in the High Castle creates as disturbing a counter-factual America as Kevin Willmott’s mock vision of a South victorious in the Civil War, C.S.A. Franklin D. Roosevelt has been killed by the same assassin’s bullet that missed him in “our” 1933, and after a subsequent cascade of historical divergences, the Japanese rule the west coast, a German puppet regime governs the eastern states, and a demilitarized zone encompasses the Rockies. Slavery is legal, the Nazi genocide of Jews continues in America, and the Germans have destroyed Africa in a horrific spasm of racist imperialism.

Thus vanquished, ordinary Americans struggle on as second class citizens, turning for guidance to the I Ching, an ancient Chinese oracle whose wisdom, in the form of opaque, poetic passages, can be divined by tossing coins or manipulating yarrow stalks. Another mysterious book seems to be on everyone’s mind, as well: a novel called The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, which presents a strangely realistic mirror world, in which the Allies won the war, and whose author, the so called “Man in the High Castle,” lives secluded in a mountain fortress, toward which a dreamlike pilgrimage provides much of the action in the book we’re reading.

If that’s not enough book-within-a-book for you, Dick used the I Ching to write The Man in the High Castle, so while we sometimes hear an author say that a book “wrote itself,” this is the only book I know of written by another book.

Dick was not afraid to accept the help; he would later draw inspiration from an extraterrestrial consciousness he called VALIS (Vast Active Living Intelligence System) with whom he claimed to communicate directly, and his 944-page Exegesis, not exactly a cover-to-cover read, veers between coherent and bat guano bonkers.

Dick struggled with those extremes in his own life, an eventful tangle of Benzedrine-fueled word binges, financial woes, failed marriages, and a suicide attempt. The Man in the High Castle, published in 1962, won the Hugo and is generally considered to be the masterpiece among his many novels and short stories. That body of work may have spawned more films than any other, including treatments by such heavyweight directors as Richard Linklater (A Scanner Darkly), Steven Spielberg (Minority Report), and Ridley Scott, who is executive producer of the new Amazon adaptation, and whose Blade Runner is based on Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

I’m not sure what I like most about The Man in the High Castle: it’s at once a straightforward suspense novel, historical thought experiment, and morality play. But most of all it’s just plain weird, and gets you pondering all the many ways things could have turned out, for your country or yourself, but for a bullet’s straying a few more feet, a help wanted ad ignored, an email unsent. I think of my wife’s grandfather, who survived a bad Nazi shot to appear in a photo seven decades later with his 12 great-grandchildren, my son and daughter among them. I think of all my own decisions, accidents, and accidental decisions since the last time I read The Man in the High Castle, and wonder what other alternatives may be playing out through time in universes unseen.

Then my head starts to hurt. I write “2015” in my old copy and put it back on its basement bookshelf. Better leave questions like that to the I Ching.

–Dan Coleman is a Collection Development Librarian at Lawrence Public Library.

Add a comment to: The Tao of Another Now