The other day at breakfast, I quizzed my kids on weasel scats. They are age seven and nine, and potty humor is their thing these days, so I figured they would really dig Figure 22 of A Field Guide to Animal Tracks, by Olaus J. Murie: “Droppings of the weasel family, in proportionate sizes.” Surprisingly, they didn’t. The table quickly cleared, yet another reminder why my great experiment in home schooling crashed and burned, and how sick of each other we all are after six months of pandemic.

“What’s the matter with you guys?” I said as they walked away. “Last year you would have eaten up something like weasel scats.”

Crickets. After all this time together, the last thing we need around here is another dad joke. I could use a little space myself, so back to this amazing book. I checked it out after my friend and fellow LPL-er Jake showed me a photo of a mink he had seen in the Baker Wetlands in August. My family’s chances of seeing such a thing are small due to how loud we are these days, but we could at least come prepared to look for mink sign. This book has not one, but five drawings of mink tracks (including two different running track patterns), and, of course, mink scats (at 2/3 actual size, and wow, like the bumper sticker says of our great state itself, “bigger than you think!”).

A Field Guide to Animal Tracks

Minks in Kansas. Who knew? And a mile from my house! This type of information has kept me going all year, and Murie’s book of tracks and scats is one of a string of guidebooks I have pored over lately. I am most addicted to the ones with little maps of Kansas showing which counties in the state have confirmed the presence of each species. Sure enough, the mink entry in Mammals in Kansas has a tiny dark circle in the middle of Douglas County, and notes that the mink is “nocturnal and crepuscular.” The latter word indicates a preference for twilight as well as night, and is a new one for me, but one you can be sure I annoyed my kids with for a few days after I looked it up, just as I have tormented them with my Kansas field guides all year. Here are some of the best of those, along with a few of my favorite discoveries within:

If you live in Lawrence, it is possible, within a few minutes from home, to see a pelican filling its pouch with gallons of water, or an osprey holding a fish in its talons, or a painted bunting, a bird so gaudy with color it looks like it rolled around on an artist’s palette. Birds of Kansas opens up that local avian world, the most amazing thing about which is that it was right here all along. Of course, everything is more interesting if it’s like a videogame (sigh), so when my kids figured out that birds could be broken down into the same hierarchy that their favorite game, Roblox, uses for its various digital creatures—common, uncommon, rare, ultra-rare, and legendary—they started keeping their own bird lists, and I was a desperate enough homeschooler to run with it if that's what it took. The citizen science app and web site, eBird, created by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society, is a great help, too, listing as it does the observations of local birders (use species range maps to pinpoint exactly where those pelicans, osprey, and painted buntings are, and when they can be seen). Always up for a challenge, the kids picked out the greater roadrunner as the most “legendary” bird to look for in Douglas County, since one hasn’t been seen here since the winter of 1998-99, according to eBird.

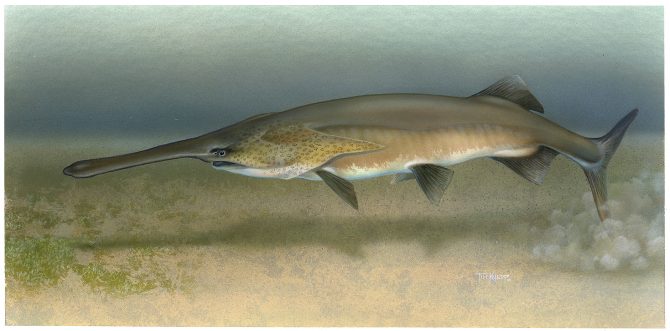

Like many this year, I rediscovered fishing as an ideal social distancing activity, and some interest seems to have taken hold in my kids, as well. When my son caught a freshwater drum this summer and I misidentified it as a common carp, I knew I needed a book, and Fishes in Kansas is it. Among its revelations are the tiny black dots in Douglas County indicating the presence of paddlefish (with typical Kansas understatement, the authors point out that “no other fish in North America remotely resembles it”), chestnut lamprey, and American eel, any one of which, were I to pull it up from the deeps, would probably cause me to pee in my pants. The American eel entry is the most amazing, especially in light of the fact that over the summer a member of a large regional fishing group on Facebook posted a photo of himself having just pulled a rather long one of those from the Missouri River at Kaw Point, in Kansas City. Stunned, I turned to it in the book and read one of more poetic passages I’ve ever read in a field guide: “No eels ever began life in Kansas, although eels formerly occupied streams throughout the state. Their initial habitat is more than 3000 miles away, in black, cold water more than a half mile deep in the Atlantic Ocean, where their parents go to spawn and die.” Turns out, the life cycles of the American eel and its European cousin are among biology’s great unsolved mysteries, and as luck would have it, The Book of Eels, a brilliant new memoir published this summer, carries on in the same spirit of fateful wonder as that guidebook passage for 250 more pages, chronicling what we do know, how it was learned, and the author’s experiences fishing for eels as a boy in Sweden with his father. It’s the best nature memoir I’ve read since Helen MacDonald’s 2014 instant classic, H is for Hawk.

Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines in Kansas

In 1966, the University of Kansas hired Homer A. “Steve” Stephens, an Emporia botanist, to collect plants for study. Over the next decade, in one of the greatest feats of research I’ve ever heard of, he travelled throughout the Great Plains in a converted botany-mobile, and is said to have visited every county from Texas to the Canadian border in his quest to collect some 90,000 specimens. These became the core collection of the R.L. MacGregor Herbarium at the University of Kansas, one of Lawrence’s unsung treasures, as well as collections at Emporia State and the University of North Carolina. Stephens also penned what might be the Moby Dick of Kansas field guides, his 1969 Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines in Kansas. Fifty years later, KU scientist (and herbarium curator) Craig C. Freeman and K-State librarian Michael John Haddock revised and expanded it, added hundreds of beautiful color photographs, and made both of my kids cry when I forced them to identify all the trees in our yard and declare their favorite Kansas shrub. For my part, I used it to help track down my favorite native tree, the paw paw, and harvest a few of its amazing, custard-like fruits to make a pudding, which my kids then refused to eat.

“That stuff gives you gas, Dad.”

“Ah, yes. Well,” I say. “Freeman and Haddock have that covered. It says here, ‘care must be taken when handling or consuming the fruits, which can cause contact dermatitis or sometimes severe gastrointestinal pain.’”

Eye roll.

Did I mention we’ve all been together too long? These days I often wonder, did they learn anything in our six months of home schooling, besides new ways to walk away, or what it looks like when a grown man has a temper tantrum? They didn’t do much math, and most of the time it was just me doing the reading. So many of my big project ideas came to nothing, but one thing I did do right. They know now there is at least this when your world shrinks, and so much in it is sad: You can see it in a book, then go out there and find it. The bird. The fish. The bright green gem between the leaves. Solace.

-Dan Coleman is a Collection Development Librarian at Lawrence Public Library.

Add a comment to: Survival Guides